Anyone Can Be a Visionary Educational Leader— But They Must Move Beyond “Management”

It’s been three years since I’ve become a professor of “educational leadership,” and here’s what I’ve learned about the topic.

In the fall of 2021, I began my first tenure-track professorship at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami, Florida. Specifically, I became an assistant professor of “Educational Leadership,” appointed to a program where we train educators and administrators to shine as leaders across various positions in education. Most of our students are professionals serving Miami Dade County Public Schools (MDCPS), the third-largest school district in the US.

Outside of teaching, I research leadership and student achievement, specifically how leaders help young people of all backgrounds thrive. Being in Florida (as you can imagine) provides an interesting backdrop. On my Substack, I’ll share lessons on transformative educational leadership in challenging and sometimes even hostile times.

Today’s post is about one of the most important takeaways I’ve learned when it comes to making progressive change in and around schools.

Leaders Must Move Beyond Maintaining and Managing Schools

Most of the research on how to effectively run schools and school systems centers around managing various systems and processes. It can be technical. School staff need to get along, get paid, and teach to the best of their ability. Students need to be safe, be nurtured, be taught, and yes, also “managed,” so that everyone can mesh under a thriving culture. All under a tight budget.

But the problem is, this is not the status quo. Accomplishing all of the above is not only hard work, it is rare. You can’t get these outcomes by simply managing and maintaining. Managing and maintaining keeps unequal systems in place.

You can’t get these outcomes by simply managing and maintaining. Managing and maintaining keeps unequal systems in place.

On a whole, schools today are more segregated racially than before the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, deeming separate but equal unconstitutional. At the same time, the US is rapidly diversifying, signaling that we are increasingly isolating ourselves into more homogeneous echo chambers.

Within this landscape, achievement plays out along lines of race and class. For the first time in US history, the majority of kids are coming to school from lower-income families. Poorer children attend poorer schools and rarely climb out of their economic bracket. Childrens’ birth zip codes and their parents’ level of education are the strongest predictors of their future success.

Schools could fix all of this, and create a more cohesive melting pot, where all young people come to thrive, but only if we let them-- and only if educational leaders disrupt the status quo.

When leaders see their job as disruptive, and lean into this, they thrive. They must, on some level, see their work as insurgent, or rebellious, to promote fairer opportunities for all.

Everyone Can and Must Be An Educational Leader

Anyone can disrupt the deep, structural challenges that permeate education.

One of my students at FIU, Debra Bazile shows us how. Debra started her teaching career at Broadmoor Elementary in Little River, Miami -- a Title 1 school serving predominantly students of color from low-income families. Debra’s students loved story time in class, largely due to the representative and multicultural books she read. Debra decided to create a class library and let her students check out books from the classroom, take them home, and then bring them back to exchange for another book.

Soon though, a problem emerged: the books were going home, but they were not coming back to school.

Debra asked herself, “Why is this happening?” She could have found fault in her students-- thinking they were stealing or that their parents did not teach them about the boundaries of personal belongings -- but she instead looked for fault in the system. Again, it’s the system that needs to be disrupted.

Debra started with the obvious: her students must not have had books at home. And yet, they loved trying to read. This was to be celebrated, not punished.

Debra identified her students’ lack of books as an “opportunity gap.1” Rather than take books away, she chose to fill this gap through adding more books to the situation. Debra partnered with local libraries to get more books donated to the class. She organized a field trip for her students and their parents to get library cards. She increased their agency to help themselves.

Now the children did not fear that the books would run out. All the books returned to class and the classroom library became more vibrant, exceeding Debra’s expectations.

Debra unleashed her students’ promise, when others may have limited it instead. She demonstrated the kind of disruptive leadership that today’s schools need.

The key lesson here is that anyone can be an educational leader. In fact, we need them to. Everyone must step up across education- from students and parents, to educators, to organizational leaders. Everyone has strengths and talents to offer our broken educational systems in order to fix them and encourage all children to thrive.

The cohesiveness of our future society depends on a flourishing education system. Through education we directly shape the communities we inhabit. Let’s each do our part to make both of them brighter places for everyone.

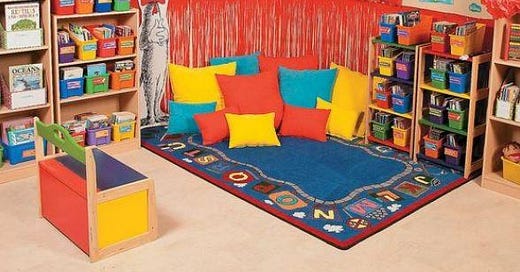

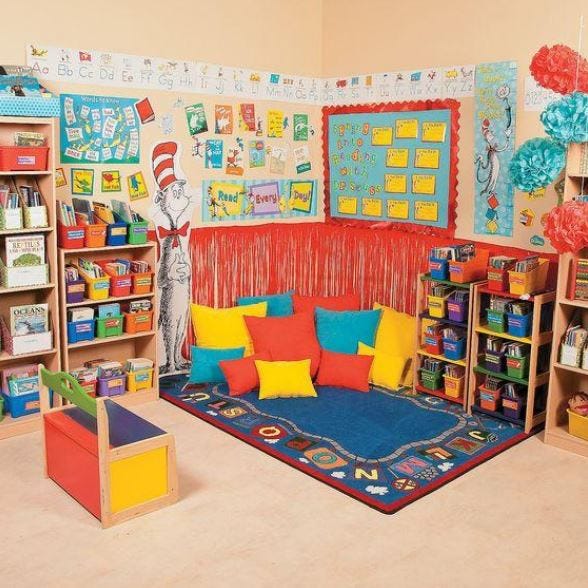

***If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating a few dollars to Ms. Debra’s reading nook for her 1st graders for the 2024-2025 academic year. Here’s a note from Debra directly:

Donors Choose Project: "Creating A Cozy Book Nook For First Graders"

“Support my first graders' love for reading by helping create a cozy nook where they can practice reading fluency and enjoy books. Your contribution will make a big difference in their academic growth!”

“Opportunity Gaps” refer to the way arbitrary and inherited factors (income, race, networks, neighborhoods) affect outcomes. Today, a student’s birth zip-code and their parents’ level of education are better predictors of their future than anything about the child or their school. This represents an education opportunity gap at large.