We Have to Transform Our Idea of Who an "Educational Leader" Is

In 2020, a single mom reached out to me to speak about my work. Unknowingly, she inspired my next research project and forthcoming book on educational leadership

In January 2020, before pandemic altered the earth’s tilt, I received a message from a woman named Denise Williamson. She had just watched my recent TED Talk and felt the need to reach out.

My argument in that talk was this: We need an all-hands-on-deck approach to education to break cycles of inequality. Supporting marginalized students and communities, I said, actually strengthens our economy and civil society. Schools are the one place we must be more socially minded; our free-market systems have led to individuals focusing on enriching themselves at the expense of caring for others and creating a whole that works for everyone.

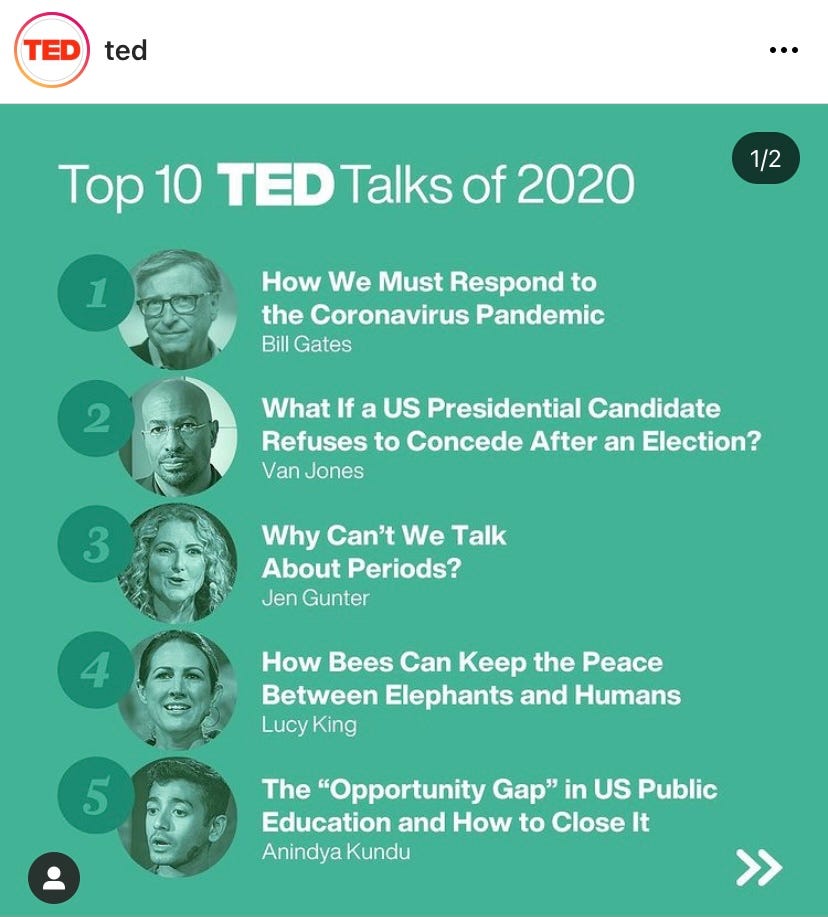

My talk, “Closing the ‘Opportunity Gap’ in US Public Education” became the 5th Most Popular TED Talk in 2020. Somehow, I wound up on a graphic with Bill Gates.

With exposure came comments and critiques, but I’m no stranger to criticism especially from those who’d rather maintain the false comfort of the status-quo. Some part of my remarks struck a chord with Denise, a single parent of two Black girls. Denise went straight from my video on TED.com to my website and left this message on my Contact Me page:

Would you please call me? . . .. I am a minority and an only parent of 2 school-aged kids. I want to verbalize my comments to your recent TED Talk on closing the achievement gap. As you indicate, access to opportunity is low and I am busy working full-time and raising children. I don’t have time to communicate via comment pages. Thanks, Denise.

My mission is to champion greater collective responsibilities and accountability in education to benefit all children and thus our future. Some take this to mean I don’t care for individual responsibility, talent, or effort in determining success. Or that I am against healthy competition.

As anyone who has shared a talk, article, or even TikTok video with the internet knows, the comment section can be brutal. I remind myself that touching these nerves may indicate I’m scratching the surface of a broken system.

Still, something told me to call Denise and hear her out. (And to this day I can’t help but smile to myself at the last line in her message—that she “does not have time to communicate via comment pages” — which sounds like she is reprimanding me for not being more accessible to busy people like her.) But she was telling the truth: between raising her daughters and working full-time, Denise’s time was limited. And yet she still reached out.

And so, I picked up the phone and nervously dialed Denise ‘s number.

Denise sounded surprised when I introduced myself, and then we sat for a moment in awkward silence. She did not think I would actually call. She thought had shipped a futile paragraph into the vast expanses of the Internet.

After breaking the ice, we ended up chatting for over thirty minutes. Denise told me her story which revolved around her two daughters’ denial of educational opportunities in Indianapolis. Denise was tired from an endless battle for her daughters’ education when she came across my speech. Denise’s full story is featured in the Introduction of my forthcoming book, Transforming Educational Leadership (Fall, 2025; Oxford Uni Press).

For now, the gist is that Denise’s daughters experienced racist sorting – a typical practice across US schools – whereby they and other deserving minority students were blocked from entry into an overwhelmingly White honors programs. Denise’s eldest, Nicole had straight A’s in 5th grade and her teacher, a US Presidential Teacher of the Year Winner, recommended her for Honors classes at the middle school. But this request denied without explanation once she arrived at her new school.

Denise described how she noticed the ongoing, racial tracking problem and how she fought it, tooth and nail. Eventually, she got her daughters into the right classes and on an academically challenging track. But the experience left her dispirited and dismayed towards the educational system at large.

I’ve spent my career thinking about why our education system works so hard to keep us separated by arbitrary divisions, including our race, our income, and our lifestyle. For example, why are our schools, 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education, more segregated today than before that landmark decision?

Despite her daughters’ eventual success, Denise naturally lamented that her painstaking efforts did not create lasting and systemic changes for other deserving students. After we hung up, I found myself ruminating.

Denise’s efforts deserved to be chronicled—to be documented to inspire others. Denise’s story helped me realize that an important aspect of educational leadership was being ignored: individuals and communities can and must constantly resist oppressive forces– those which impede schools from achieving their potential of promoting opportunity for all – to actively promote a more “desegregated” ideal.

A desegregated ideal would be one where no student experiences additional barriers due to inherited and arbitrary factors about who they are, where they live, and what their families look like.

Advocates like Denise face the system to change it for good. They and their stories are not readily found in the published materials used to train educational leaders.

That is what compelled me to write my next book, Transforming Educational Leadership, to broaden the definition of who educational leaders are. Through research, I’ve gathered examples and data of unorthodox leadership at all levels—parents, students, educators, leaders, policymakers, and community members — to show that everyone has to be a leader, in and around education, to remedy our failed democratic promises and live up to our potential as a nation.

Schools provide the pathway and need all of us to pitch in.

My book sounds this alarm.

Because if we don’t fight for ourselves, who will?

Dr. Kundu is an assistant professor of educational leadership and policy studies. He is a sociologist who researches student agency and approaches within educational leadership for reducing inequality in and around schools. His next book, Transforming Educational Leadership will come out in the fall of 2025, published by Oxford University Press.