Stepping Down to Stand Up: How Pedro Noguera Resigned in Order to Disrupt Inequity

Pedro Noguera has a long track record of advancing equity through his work. Here is one such defining story from his career.

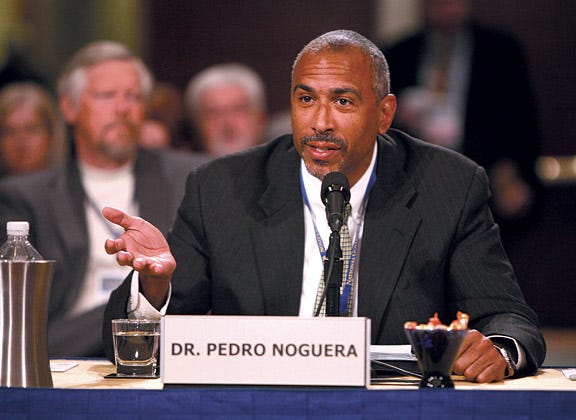

Dr. Pedro Noguera is currently the Dean of the USC Rossier School of Education and a leading US expert on the achievement gap and inequalities in public education. Noguera has built a career focused on improving access to opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds. He is also one of my closest mentors, and a participant of mine in my educational leadership research and forthcoming book. The following is a recounting of one of his stories*.

During Noguera’s time as a professor at New York University (NYU), he also served as a Trustee for the State University of New York (SUNY) from 2011 to 2014. In this role, he chaired the Charter School Authorization Committee.

New York State’s charter schools are overseen by the New York City Department of Education and the SUNY Board. These organizations evaluate applications for charter schools, which operate with more independence than traditional public schools. Schools must be re-evaluated periodically to decide if their charters will be renewed. For the most part, Noguera felt that the work being done was equitable and just.

However, his perspective changed with one case involving an all-girls charter school on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Initially supportive, Noguera reconsidered his stance upon visiting the school grounds and realizing that the charter school was located in a building previously used by a public school serving underprivileged children. Noguera began to question whether these charter school students deserved the space more than the original students.

In an interview, Noguera recounts the episode: “And then it turned out that most of the girls who attended this school were fairly middle-class. Their parents drove them there, they didn't have to rely on public transportation, and they were better off than the kids in the projects. So, the question was, “Why did they deserve that building more than the kids who historically had it?”

Most students at the charter school came from middle-class backgrounds, leading Noguera to question whether they deserved the space more than the original students.

This case represented one of many.

Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, more than 200 public schools were closed, and smaller schools, many of them charters, were opened in their place. This strategy raised concerns about displacement. In the same building as the all-girls school, a special needs school was also housed, and both schools faced potential relocation if the charter was not renewed. Noguera expressed concerns about the broader implications of these decisions but found that as a charter authorizer, his influence was limited to the merits of the charter itself, not the location or impact on other schools.

“I can't just look at the charter and not think about the implications of what's going to happen [from our decision],” says Noguera. And so, I did a very public resignation which got published. I explained how charters were being used. [This case] exposed the way decisions about real estate, and who had access to it, were becoming equity issues impacting students. It tended to be that charter schools were displacing schools serving in many cases the most disadvantaged kids.”

Noguera felt the only way to impact change was through stepping down from his post and drawing attention to these issues. In his resignation, he critiqued the way charters, often run by predominantly white boards from hedge funds and banks, were displacing schools serving disadvantaged students. He believed that those closer to the communities being served should have more say in the process.

Although Noguera did not (and still does not) entirely oppose charter schools, he recognizes the complexities surrounding their approval. He maintains a nuanced position on charter schools, rejecting a binary "for or against" stance, which distracts from the broader social implications of these cases.

Ultimately, Noguera’s story is one of resistance: Often, in order to disrupt an inequitable status quo, we must act in disruptive ways. There is no point in harmony if we cannot achieve equity for all.

Anindya Kundu

*If you enjoyed this story, subscribe to my Substack and keep an eye out for my forthcoming book, The Power of Educational Leadership (Oxford University Press, 2025). There, I share more than 30 similar stories how leaders promote equity despite various structural-level obstacles.

Anindya Kundu is an assistant professor of Educational Leadership and the author of The Power of Student Agency (2020). Follow Anindya on Twitter or LinkedIn.